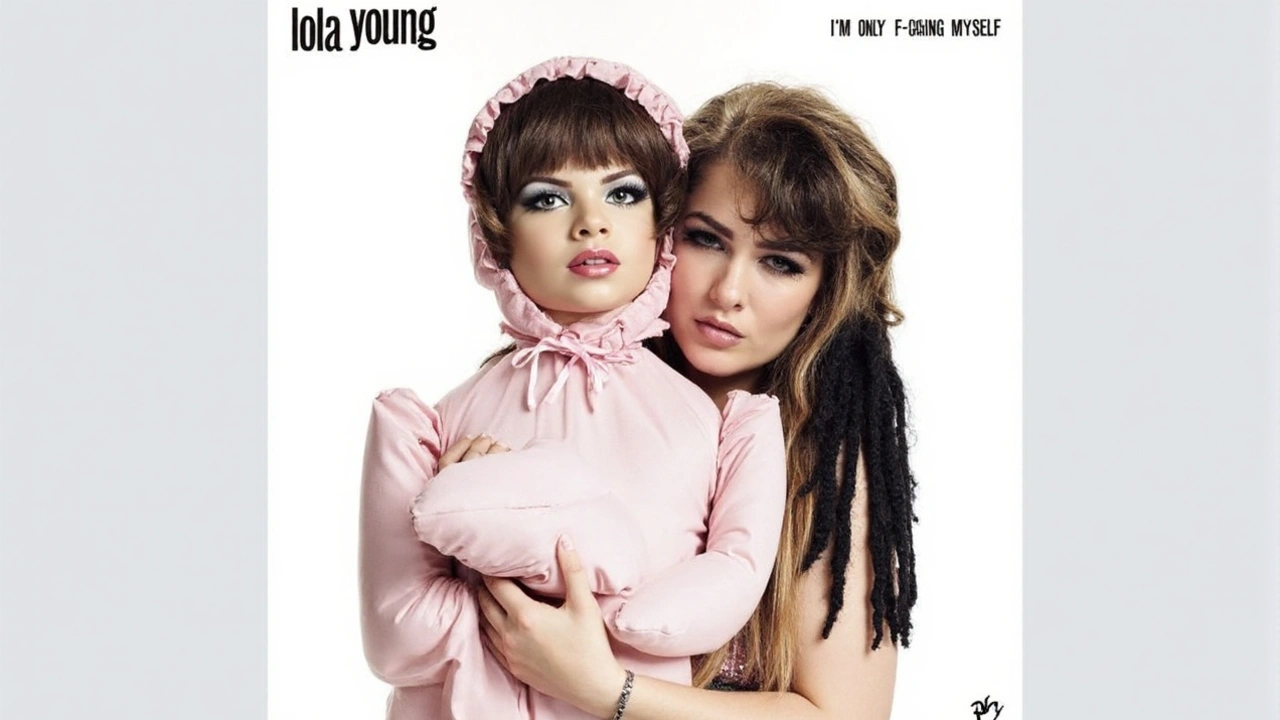

A pop album that refuses to flinch

A pop record called “I’m Only F—ing Myself” is not trying to play nice. It arrives with teeth bared and nerves exposed, and that’s exactly how Lola Young wants it. The British singer’s new album is the sound of someone telling the truth before she’s figured out how to package it. No gloss. No tidy moral. Just the mess—and the music—of getting clean, slipping, and still wanting love and sex on her own terms.

The timing is stark. Young went into rehab for five weeks in November 2024 to confront a cocaine addiction. Those sessions don’t sit quietly in the background here; they sit in the front seat. She writes as if the studio is a confessional and the mic is a witness. The result is an album built from raw admissions, ugly jokes at her own expense, and a refusal to make her story palatable for playlists.

You hear it instantly on “Not Like That Anymore,” where she calls herself “a dumb little addict” and talks about quitting “the snowflake.” It’s bracing, and sometimes it’s hard to listen to. That’s the point. Young isn’t glamorizing the spiral; she’s documenting it. There’s a difference between shock value and consequence, and she keeps steering toward the second one.

That honesty lands even harder because it’s not theory—it’s her life right now. She pulled out of a Tonight Show slot in July after a relapse, a public stumble that strips away the usual pop-star fantasy of clean arcs and easy comebacks. The album feels like it understands that. Recovery isn’t linear, and she doesn’t pretend it is. She gives you the nausea, the bargaining, the relapse math, and the defiant humor you need to face another day.

“d£aler” is the album’s tightrope act. The guitars run hot, the drums snap, and the fantasy of flooring it down an empty highway keeps colliding with the memory of the person she can’t quite quit—the plug, the fix, the escape. It’s the push-pull of the whole project: freedom fighting dependency in real time, often in the same verse. Sonically, it’s one of the clearest statements here. It suggests Young can carry a rock-leaning lane without losing the hooks that got her noticed.

The other thread is sex. Young refuses to apologize for wanting it, liking it, and saying so out loud. That territory has tripped up plenty of artists—either it gets coy or it turns into a brand. She steers somewhere more human. The explicit lines hit like part of the life she’s describing, not a trick to turn heads. It makes the intimacy feel lived-in instead of staged, even when the details are uncomfortable.

An album born from recovery—and the identity question that follows

Musically, the record splits the difference between pop instinct and grit. You get lean guitars and bruised pianos, the kind of drum programming that thuds in your chest, and pockets of space where her voice sits bare. The production lets the vocals carry the weight; there’s no rush to smother the edges. She’ll rasp, crack, and then soar half a verse later. The shape-shifting works because the writing keeps you grounded in the moment she’s living.

Is it tidy? Not at all. Reviewers have called it “teetering on the knife edge of greatness,” and you can hear why. The album isn’t chasing a single identity; it’s arguing with itself about one. Some songs feel like late-night diary entries, others like stage-ready detonations. That tension is part of the pull. You’re not getting a brand rollout—you’re getting a person mid-pivot.

That can frustrate listeners who want a lane. But when an artist chooses honesty over image, the map gets redrawed in real time. Here, the sequencing leans into that flux. The early stretch sprints—fast tempos, sharper edges—before the second half lingers on consequence and the quiet after the chaos. You can sense the team kept the polish light, which is rare in a streaming world that favors everything loud, compressed, and hook-first.

There’s a broader music story hiding inside this one. Pop has cycles of confession—Demi Lovato’s unsparing ballads, Amy Winehouse’s diary-to-vinyl candor, the way a generation after Billie Eilish normalized saying the quiet part out loud. Young is entering that conversation with her own angle: less victorious comeback, more dispatch from the front line. It’s not about tying a ribbon on survival; it’s about singing while you’re still stitching.

What about the singles? The obvious pick is “d£aler,” which has the tempo and the tension to cut through. “Not Like That Anymore” is the gut punch that will travel in clips and captions. Radio edits will be messy—this album doesn’t flinch from language—but the streaming ecosystem doesn’t punish that the way it used to. If anything, the unfiltered lines make the songs more shareable because they feel uncoached.

Then there’s the career calculus. A late-night TV cancellation isn’t just a headline; it’s budget, momentum, and a cold reminder that health comes first. Expect the rollout to flex week to week: small rooms instead of arenas, tighter sets, and people around her who understand that a great show is sometimes the one you choose not to play. If she threads that needle, the live translation could be powerful—these songs are built to ricochet in a room.

Does the album solve the identity debate? Not really, and that’s okay. You can hear a rock record trying to break through, a pop record that refuses to be cute, and a songwriter who trusts her gut more than a genre. The writing is the anchor: specific, a little feral, and allergic to euphemism. When she leans into that—when the lyric owns the room—everything else feels secondary.

The risk is the point. Plenty of artists take confessional swings and end up with mood boards. Young brings receipts. The relapse, the rehab, the desire that won’t die, the shame and the jokes that smuggle you through the worst nights—it’s all here. That’s why the album lands even when it’s uneven. It’s not performing honesty; it’s living it, with a mic on.

If you’ve been waiting for a pop record that doesn’t tidy up the mess, here it is. “I’m Only F—ing Myself” doesn’t offer clean arcs or last-page wisdom. It offers a pulse. It sounds like the truth you say to a friend at 2 a.m., the kind you regret texting and then feel relieved is finally out. That’s the wager this album makes: tell it straight, make it sing, and trust that being real is its own kind of hook.

Kathryn Susan Jenifer

Oh, because nothing shouts “I’m fine” like screaming about your own rehab on a pop beat, right? The drama is so thick you could cut it with a butter knife, and I’m just sitting here with my popcorn, waiting for the next self‑destruct note.

Jordan Bowens

Wow, talk about a musical middle finger to the industry.

Kimberly Hickam

Let’s break this down like a textbook on modern confessionals set to a synth‑driven heartbeat. First, the album’s premise is not a gimmick but a raw telemetry of a lived experience, which immediately places it in a lineage that includes Lovato’s catharsis and Winehouse’s diary‑turned‑vinyl. Second, the lyrical architecture refuses to hide behind metaphorical sugar; it spells out addiction with the bluntness of a clinician’s report, making the listener both a confidante and a witness. Third, the production choices-sparse piano interludes juxtaposed with jagged guitars-serve as auditory stethoscopes, listening to the patient’s pulse in real time. Fourth, the narrative arc mirrors the neurochemical rollercoaster of withdrawal: anticipation, dread, brief euphoria, and the crushing comedown. Fifth, each track is arranged to mirror a therapy session, with verses acting as the patient’s monologue and choruses as the therapist’s challenging refrains. Sixth, the vocal delivery oscillates between a cracked whisper and a soaring scream, embodying the dichotomy of fragility and defiance. Seventh, the interludes are not filler but deliberate silences that mimic the uncomfortable pauses in a real conversation about addiction. Eighth, the album does not offer tidy redemption; instead, it leaves the story open‑ended, reflecting the ongoing nature of recovery. Ninth, the inclusion of explicit sexual imagery is not mere titillation but a reclamation of bodily autonomy that many recovering individuals grapple with. Tenth, the track sequencing intentionally places the most abrasive songs early, forcing the audience to confront discomfort before any soothing lull. Eleventh, the lyrical motifs of “plug” and “fix” serve as recurring leitmotifs, reinforcing the theme of dependency. Twelfth, the use of unconventional symbols like “d£aler” is a visual representation of the fractured identity the artist experiences. Thirteenth, the album’s refusal to sanitize language challenges streaming platforms’ algorithmic sensibilities, making a political statement about artistic integrity. Fourteenth, the collaborative production team appears to have taken a minimalist approach, allowing the raw vocal takes to dominate the mix. Fifteenth, in an era where pop often hides behind glossy veneers, this record stands as a stark, unapologetic mirror, demanding listeners to acknowledge the messiness of humanity.

Gift OLUWASANMI

While you’ve dissected the anatomy of the record with surgical precision, you oddly overlook the fact that the sonic aggression sometimes feels like a therapist shouting over the patient, which can be counterproductive to genuine healing. The relentless “hard‑edge” aesthetic, though intentional, risks alienating listeners who might benefit from a softer entry point into the conversation about substance abuse.

Keith Craft

Ah, the tragedy of art masquerading as therapy-how delightfully melodramatic! One can almost hear the curtain rise as the protagonist clutches the mic like a lifeline while the orchestra of despair crescendos, begging the audience to feel the weight of every shattered promise.

Kara Withers

For anyone listening who might be curious about actual resources, it’s worth noting that organizations like the NHS Substance Misuse Service in the UK, or SAMHSA’s helpline in the US (1‑800‑662‑HELP), provide confidential assistance. Moreover, peer‑support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous offer a community that understands the relapse‑recovery cycle described in the album. Engaging with a therapist who specializes in addiction can also help translate the raw emotions of the music into actionable steps toward sustained sobriety.

boy george

Indeed, practical help often gets lost amid the theatrics.

Cheryl Dixon

Honestly, the whole “confessional pop” trend feels like a marketing ploy, a way for labels to cash in on trauma without offering any real support to the artists.

Charlotte Louise Brazier

That perspective misses the point that sharing personal struggle can empower listeners to confront their own issues, turning a private battle into a collective conversation.

Donny Evason

From a cultural standpoint, the album builds a bridge between the individual’s psyche and the societal narrative around addiction, challenging the stigma by embedding vulnerability directly into mainstream soundscapes-a move that can shift public perception in a meaningful way.

Phillip Cullinane

While the emotive power of the record is undeniable, it’s also important to recognize the potential mental health impact of repeatedly exposing listeners to such raw depictions of relapse; repeated activation of neural pathways associated with trauma can exacerbate cravings or depressive symptoms in susceptible individuals, so coupling the listening experience with professional guidance or self‑care strategies is advisable.